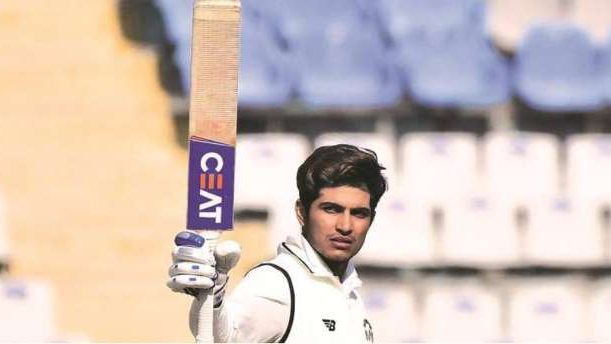

Shubman Gill: From digging Virat Kohli’s scores to joining him in dressing room

Gill has got help from many — Rahul Dravid sorted out his backlift throughout an ‘A’ tour — and success now would perhaps rely on how the Indian group makes use of him.

Even cricket journalists aren’t as regular site visitors to the cricketarchive site, which archives ratings of membership and domestic games, as Shubman Gill. Every now and then, he would land up on that site, digging dim games that Virat Kohli or Rohit Sharma or Cheteshwar Pujara had performed when they were at the U-16 or U-19 level.

“Especially Kohli. Yaar Virat Kohli jab sixteen or 19 years tha, to kya karta tha? (what did he do?) How many runs he used to make? I would open up his document and check!” Gill as soon as advised this newspaper. “Achcha itna… inse to hamara zyaada hai yaar! Matlab sahi ja raha hai!” (Ah, These many… I have greater runs than him. It means it’s going well!).

That curious boy with his pleasant cocktail of innocence and ambition will now be sharing the equal dressing room with them.

During chats, he once said something as a substitute startling so flippantly that it made one sit up. “I have by no means failed three games in a row.” Never? “No bhai.” How would you react if that occurs as it’s certain to as you pass up the grade? Will you be okay? Laughter. “Socha nahin! I would cope with it then. Don’t worry.”

And so, one dials former India cricketer Karsan Ghavri, who used to mentor an 11-year-old Gill and used to be instrumental in getting him into Punjab U-14 teams.

“Oh, he is right,” Ghavri says on the day Gill is selected for India’s Test squad against South Africa. “He is a specific cricketer, haven’t considered him fail too many video games in a row. And he is temperamentally so sound, that one doesn’t have to fear about him.”

For a boy who possessed all the pictures – even the pull, courtesy his father asking his farm helps to jump at him again and again and paying a hundred rupees to each person who bought him out at his domestic — it was once the way he left the ball, that caught Ghavri’s attention.

Ghavri was once overseeing an u-19 pace camp at the PCA stadium in Mohali when he noticed the little boy, about eleven or 12 years of age, playing at a small floor contrary the stadium. Ghavri desired extra batsmen to face his bowlers and impressed with Gill, requested his father to send him to practice.

“It was a pure tempo camp and the 18-19-year-olds I had were all out to provoke and they bounced the kid. He would pull the ball, sway from a few, protect solidly, but the way he left the ball outdoor off impressed me. It would have been comprehensible had the boy tried to impress and try to play a shot to each and every ball, as children commonly do. But he played so exact that I was left admiring,” Ghavri says.

It used to be Ghavri who planted the trust that Gill may want to one day play for India. “Such was the intelligence and, greater importantly, his challenging work. He would come to our sessions two instances a day and work so hard. As years went by, I advised him to goal big, now not settle for less. If you can proceed be so serious about the sport and be fearless, you are going to play for India one day. He is lucky that his parents encouraged him a lot, spending so lots time and power in his cricket training.”

In these times, if one is to make it big in cricket, one has to begin very early, and have an obsessed passionate dad or mum to push and encourage. The days of taking walks through adolescence, falling in love with the game at some stage, then making an attempt one’s luck, appear gone. Gill’s father planted the seed extraordinarily early in the piece.

“Jaise bhi ho, India khelna hi hai,” (Whatever it takes, have to play for India) The Gills remembers that thought floating in his head years before. It started very young, aged four, when his father, a well-to-do landlord, threw the ball at him in village Chak Kherewala, close to Jalalabad in Punjab. The father liked what he saw, the son loved what came at him, and the father deployed his farmhands, 18 to 20-year olds, to throw balls at him. As time went, the entice of easy money, a hundred rupees, used to be lengthy gone, they now took shifts to bowl at the boy except luck. Then the likes of Ghavri got here into the picture as soon as the family moved to Chandigarh just to pursue the boy’s cricketing dreams. Not that Gill was once flailing at school: “Till eighth class, I would get about ninety per cent. Uske baad, neeche gaya (After that, it got here down).”

Gill sneezes at any sentimental concept of “lost childhood”. “I simply love this game, I love batting. It’s no longer sacrifice. It’s all choice. I had the desire to go for some masti (enjoyment) or go to practice. I chose practice.” And here he is, in the Indian Test squad.

En route, he has acquired assist from many — Rahul Dravid sorted out his backlift throughout an ‘A’ tour, and success now would perhaps depend on how the Indian group uses him, and at what role in the batting order, and how they back him. They have chosen him as the back-up opener and Ghavri feels that “he can open, he will face any challenges, he has the game, but ideally I would like to see him at No. four or thereabouts. He is temperamentally sound, has the skill, and the wish to do well. Hope he gets ample chances anyplace they play him. This boy is the actual deal.”