Oxford developed a covid vaccine, then scholars clashed over money

Early deal with Merck was scotched for fear poor countries would be left out; now university could make over $100 million with AstraZeneca if technology succeeds

Just weeks before the University of Oxford announced a mega-deal aimed at rolling out a Covid-19 vaccine worldwide, university leaders had a revolt on their hands.

Publicly, Oxford scientists were touting progress in the laboratory. But behind the scenes, two renowned vaccinologists leading the effort were fighting a proposed deal with U.S. pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co.

The scientists’ small biotech company—a spinout partially funded by Oxford—was refusing to hand over intellectual property rights. To outflank their bosses, the scientists asked a London investment banker to help explore other potential deals.

For the 900-year-old university, the stakes were as high as at any time in its modern history. As the coronavirus pandemic ravaged lives and economies around the globe, Oxford found itself ahead of the pack with an encouraging vaccine candidate. But feats of science were just part of the battle. Publicly funded Oxford needed to combine its high-minded ideals with the profit-driven ethos of the pharmaceutical world. Academics and their allies clashed repeatedly over control of the university’s strategy for delivering the jab to the world.

“We were headed into the jungle without a machete,” says John Bell, a twice-knighted Oxford geneticist tapped by university leaders to find a pharmaceutical-industry partner. “We happen to be a rather good university, but universities don’t do this stuff.”

Oxford ultimately hammered out a deal with British multinational AstraZeneca PLC to oversee the manufacturing and distribution of billions of doses. Previously unreported terms hashed out in April, described by people familiar with the discussions, including a potential royalty cut of roughly 6% for Oxford. If the vaccine passes regulatory hurdles and becomes a must-have seasonal shot, as some scientists think it might, payments could be worth well over $100 million.

The turmoil around Oxford’s vaccine deal featured on-campus clashes of ego, hastily made threats and promises, and layers of public and private investors with competing incentives.

Despite the infighting, supporters and critics alike credit Prof. Bell with bridging the divide between Oxford’s history of nonprofit medical innovation and the pharmaceutical industry’s shareholder-driven motivations.

“He can be very abrasive,” says Graham Richards, a former Oxford chemistry chairman. “He can get people very upset. But he just gets things done.”

The science behind the Oxford vaccine dates back decades. In the 2000s, Merck scientists researched using a cold virus from a chimpanzee to make any number of vaccines. Merck dropped the project, in part because it worried that a vaccine based on a chimp virus would face a difficult time getting approved by the Food and Drug Administration, according to Stefano Colloca, a former Merck researcher.

But the work continued, including at Oxford’s Jenner Institute. Named after British smallpox-vaccine pioneer Edward Jenner, it is one of the world’s foremost centers for vaccine study.

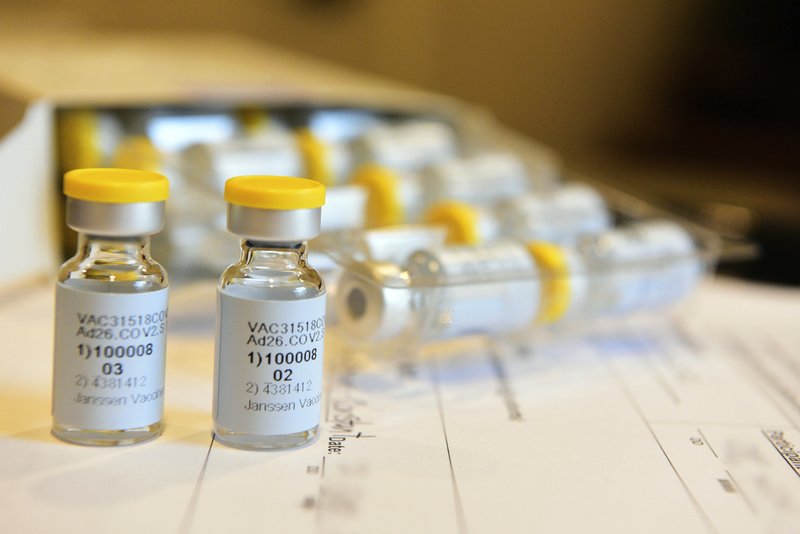

Two scientists there, Sarah Gilbert, an Oxford vaccinology professor, and Adrian Hill, the institute’s director, developed their own version of the chimp vaccine technology. They patented it and in 2016 founded Vaccitech Ltd., with Oxford’s support, to create vaccines and treatments for profit. The scientists remain at Oxford but also help oversee Vaccitech.

The biotech company was an early product of a grand Oxford experiment aimed at making the university—and the U.K. in general—more commercially competitive in technology and life sciences.

Vaccitech’s biggest shareholder is a university-backed venture firm called Oxford Sciences Innovation PLC. Oxford started the firm in 2015, attracting some £600 million from outside investors ranging from hedge funds to Chinese conglomerates. The idea was to emulate American rivals like Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by fostering profit-making lab spinouts. Oxford takes a cut of the spinouts—typically between 10% and 50%—and doles out half of that stake to Oxford Sciences. Prof. Bell sits on the venture firm’s board.